Health: (Coronavirus) Is the world winning the pandemic fight?

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESIt is little more than six months since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the arrival of a new virus a global emergency.

On that day, at the end of January, there had been almost 10,000 reported cases of coronavirus and more than 200 people had died. None of those deaths were outside of China.

Since then the world, and our lives, have changed profoundly. So how are we faring in this battle between the human race and the coronavirus?

If we take the planet as a whole, the picture is looking rough.

There have been more than 19 million confirmed cases and 700,000 deaths. At the start of the pandemic it was taking weeks to clock up each 100,000 infections, now those milestones are measured in hours.

"We're still in the midst of an accelerating, intense and very serious pandemic," Dr Margaret Harris, from the WHO, told me. "It's there in every community in the world."

While this is a single pandemic, it is not one single story. The impact of Covid-19 is different around the world and it is easy to blind yourself to the reality beyond your own country.

But one fact unites everyone, whether they make their home in the Amazon rainforest, the skyscrapers of Singapore or the late-summer streets of the UK: this is a virus that thrives on close human contact. The more we come together, the easier it will spread. That is as true today as when the virus first emerged in China.

This central tenet explains the situation wherever you are in the world and dictates what the future will look like.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESIt is driving the high volume of cases in Latin America - the current epicentre of the pandemic - and the surge in India. It explains why Hong Kong is keeping people in quarantine facilities or the South Korean authorities are monitoring people's bank accounts and phones. It illustrates why Europe and Australia are struggling to balance lifting lockdowns and containing the disease. And why we are trying to find a "new normal" rather than the old one.

"This is a virus circulating all over the planet. It affects every single one of us. It goes from human to human, and highlights that we are all connected," said Dr Elisabetta Groppelli, from St George's, University of London. "It's not just about travel, it's speaking and spending time together - that's what humans do."

Even the simple act of singing together spreads the virus.

It has also proven to be an exceptionally tricky virus to track, causing mild or no symptoms for many, but deadly enough to others to overwhelm hospitals.

"It's the perfect pandemic virus of our time. We are now living in the time of coronavirus," said Dr Harris.

Where there has been success, it is through breaking the ability of the virus to spread from one person to the next. New Zealand gets the most attention. They acted early, while there were still few cases in the country: locked down, sealed their borders and now have barely any cases. Life is largely back to normal.

Getting the basics right has helped in poorer countries too. Mongolia has the longest shared border with China, where the pandemic began. The country could have been badly impacted. However, not a single case requiring intensive care occurred until July. To date they have only had 293 diagnoses and no deaths.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES"Mongolia has done a good job with very limited resources. They did 'shoe-leather epidemiology' isolating cases, identifying contacts and isolating those contacts," said Prof David Heymann, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

They also rapidly closed schools, restricted international travel and were early promoters of face masks and hand-washing.

On the other hand, Prof Heymann argues, a "lack of political leadership" has hampered many countries where "public health leaders and political leaders have difficulty speaking together". In such a climate, the virus has flourished. US president Donald Trump and the country's top infectious disease doctor, Anthony Fauci, have clearly been on different pages, if not completely different books, during the pandemic. Brazil's president, Jair Bolsonaro joined anti-lockdown rallies, described the virus as "a little flu" and said the pandemic was nearly over in March.

Instead, in Brazil alone, 2.8 million people have been infected and more than 100,000 have died.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESBut countries that have got on top of the virus - mostly through painful, society-crippling lockdowns - are finding it has not gone away, will spread again if we relax our guard and that normality is still elusively distant.

"They're discovering it's more challenging coming out of lockdown than going in," said Dr Groppelli. "They haven't thought about how we can co-exist with the virus."

Australia is one of the countries trying to chart a path out of lockdown, but the state of Victoria is now in "disaster" mode. Melbourne went back into lockdown in early July, but - as contagion continues - has since imposed even stricter rules. Now there is a night-time curfew and people are expected to exercise within 5km of their homes.

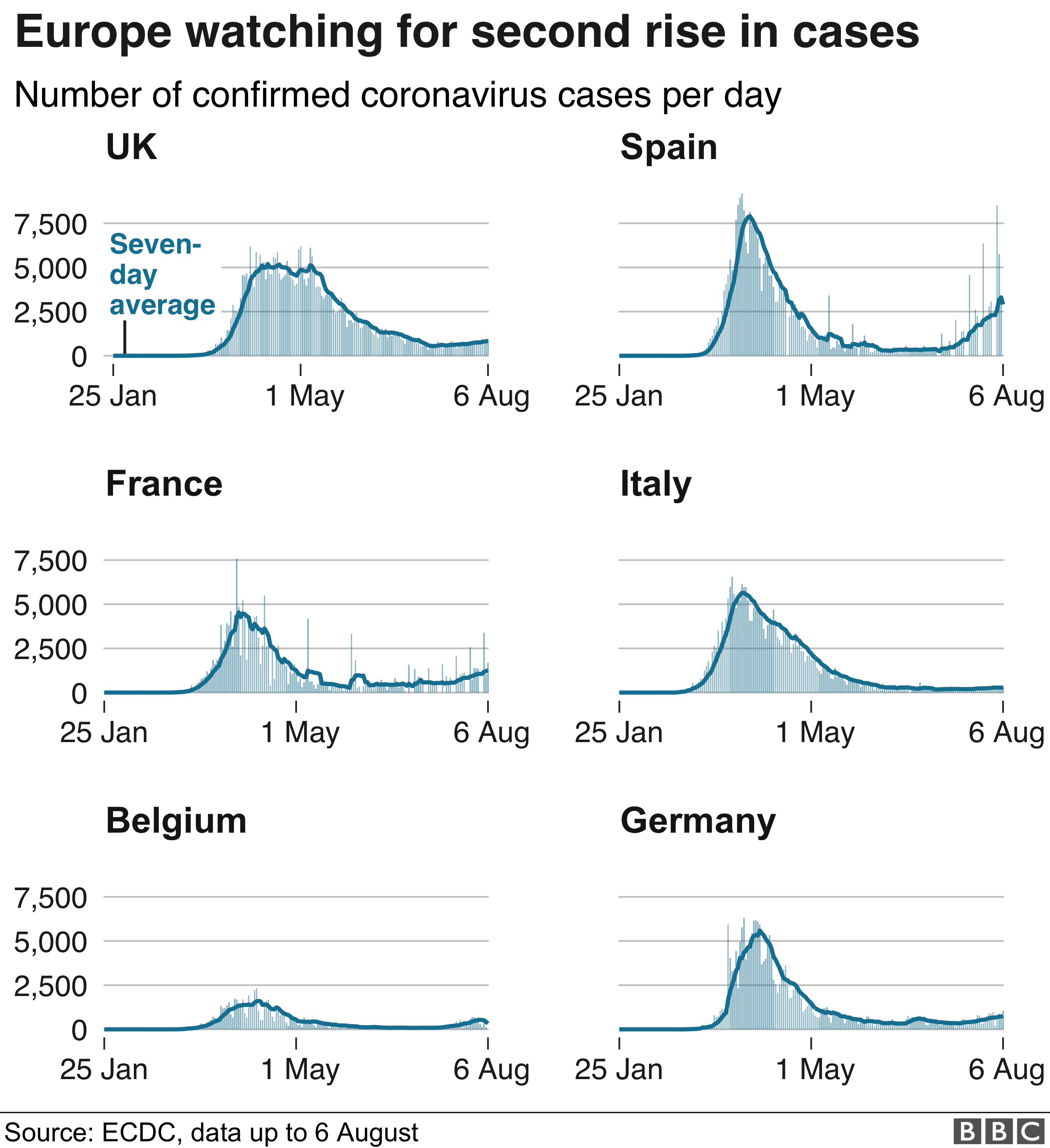

Europe too is opening up, but Spain, France and Greece have all reported their highest number of cases in weeks. Germany has reported more than 1,000 cases a day for the first time in three months.

Wearing face masks, once an oddity, is now commonplace in Europe, with even some beach resorts insisting upon it.

And - in a warning to us all - past success is no guarantee for the future. Hong Kong was widely praised for resisting the first wave of coronavirus - now bars and gymshave been closed again, while its Disneyland resort managed to keep the gates open for less than a month.

"Leaving lockdown does not mean back to the old ways. It's a new normal. People have not got that message at all," Dr Harris said.

Africa's position in the fight against coronavirus remains an open question. There have been more than one million cases; after a successful start, South Africa looks to be in a bad place, with the majority of cases on the continent. But relatively little testing means a crystal clear picture is difficult.

And there is the enigma of Africa's notably lower death rate compared with the rest of the world. Here are some of the suggestions as to why:

- People are a lot younger - the median (average) age in Africa is 19 and Covid is more deadly in old age

- Other related coronaviruses may be more common and that may provide some protection

- Health problems common to richer countries, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, which increase Covid risk, are less common in Africa

Countries are innovating in response. Rwanda has been using drones to deliver supplies to hospitals and broadcast coronavirus restrictions. They are even being used to catch those flouting the rules, as one church-bound pastor found out.

But as with parts of India, south east Asia and beyond, access to clean water and sanitation undermines the simplest hand-washing messages.

"There are people that have water to wash their hands and those that do not," Dr Groppelli said. "This is a major difference, we can pretty much break the world in two. And there is a big question mark about how they control the virus unless there is a vaccine."

- GLOBAL TRACKER: Where are the world's virus hotspots?

- LOCKDOWN UPDATE: What's changing, where?

- SCHOOLS: What is school life like now?

- THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

- UK LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

So when will all this be over?

Already there are drug treatments. Dexamethasone - a cheap steroid - has been shown to save some of the sickest patients. But it is not enough to stop all Covid-19 patients dying or to lift the need for all restrictions. Close attention will be paid to Sweden in the coming months to see whether its strategy is rewarded in the longer term. It didn't lock down, but so far has had a significantly higher death rate than its neighbours, after failing to protect people in care homes.

Generally, the world's hopes of getting life back to normal are pinned on a vaccine. Immunising people breaks the virus's ability to spread.

There are six vaccines now entering phase three clinical trials. This is the critical stage when we will discover if the vaccines that appear promising actually work. The final hurdle is also the point where many a medicine has stumbled. Health officials say the emphasis should remain on "if" we get a vaccine not "when".

Dr Margaret Harris, of WHO, said: "People have this Hollywood-esque belief in a vaccine; that scientists are just going to fix it. In a two-hour film the end comes pretty quickly, but scientists aren't Brad Pitt, injecting themselves and saying 'we're all going to be saved'."

Comments

Post a Comment